- Home

- Media Kit

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Ad Specs-Submission

- Ad Print Settings

- Reprints (PDF)

- Photo Specifications (PDF)

- Contact Us

![]()

ONLINE

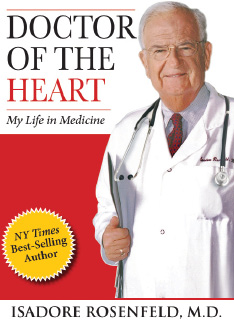

Doctor of the Heart

Editors’ Note

As a cardiologist at New York-Presbyterian Weill Cornell, a career which spans over 50 years, Dr. Isadore Rosenfeld has had a consistent focus on clinical care, teaching, and patient education. He is the Ida and Theo Rossi Distinguished Professor of Clinical Medicine. Dr. Rosenfeld has served as a consultant for the NIH in several task forces, including Arteriosclerosis, Hypertension, Special Devices (Artificial Heart), as well as on the joint Soviet-American task force on sudden cardiac death. He has been an official advisor to two Secretaries of Health and was appointed by President George W. Bush as Consultant to the White House Conference on Aging. Dr. Rosenfeld was president of the New York County Medical Society, has been an overseer of Weill Cornell Medical School for some 30 years, and was named Citizen of the World by the United Nations in 1999. He was recently elected Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Sackler School of Medicine in Tel Aviv. Dr. Rosenfeld is the author of 13 books, he coauthored a textbook in medicine, and has written 55 papers in peer reviewed journals. He was Health Editor of Parade magazine for 10 years and is currently medical consultant for the Fox News Network. The Rosenfeld Heart Foundation has supported cardiovascular research locally and abroad for almost 30 years.

You recently published what many refer to as an autobiography, Doctor of The Heart: My Life in Medicine. You’ve done a number of books throughout your career. What made you feel the timing was right for this particular book, and can you take us through the process of what it means to you?

Even before I became a doctor, I loved to communicate. When I was in medical school at McGill University in Montreal, my family had very limited resources so I earned extra money by writing for politicians. I was nominated to run for Parliament when I was in my third year of medical school. So I’ve always enjoyed communicating, and when I became a doctor, I realized how important it was for patients to understand what was wrong with them. Many patients do not. They expect the doctor to tell them what to do, and that’s unfortunate. It’s changing now. But from the very beginning, I felt it was important for patients to understand and I wanted to expand that beyond the relative handful of patients one sees in practice. So I started to write. My first book is called The Complete Medical Exam. From then on, I covered every single topic that I could think about for patients; my next book was Second Opinion, why and when you need a second opinion; after that, I wrote a book called Symptoms, what they mean; the next book was called The Best Treatment, addressing treatment options; the book after that was called Live Now, Age Later: Proven Ways to Slow Down the Clock on aging. Shortly thereafter, I went to China for our government to see about exchange of information, learned about acupuncture, and wrote a book on alternative medicine.

I thought I had exhausted all of my topics, but I have led a very interesting life and I wanted to pass the information along to my children. So I started writing this book, sort of keeping notes for them. Some of my friends saw it and they said, this shouldn’t only be for your children. That motivated me to expand it and turn it into this book.

As I continued to write it, I realized that these weren’t only stories of what had happened to me, but that in most things I had talked about, there was a message, and the basis of the message was the doctor/patient relationship, which is primary in my view. We’re doing tremendous things in medicine now, but we’re losing the doctor/patient relationship. A machine cannot replace a doctor in terms of the spiritual and the psychological support, the hope, and the relationship that exists between a doctor and a patient. That is the theme of the book.

In the book, I document many of the things that I wrote in my fact books, and that has been very well received. I paid to have this published myself. I think I will make my money back, but I didn’t write it for the money – I wrote it because people thought it would be important.

You talk of the doctor/patient relationship being lost today. How much does that concern you?

It concerns me very much. One of the reasons that relationship is being lost is time. Our society, our government, and our insurance companies do not reimburse for time. Today, it’s important to make people aware that all of the diseases we’re so good at treating with bypasses and angioplasties, for instance, can be delayed or prevented significantly, but that takes time. You have to sit and talk to a patient. But doctors have salaries to pay, rent to pay, malpractice insurance to pay, and equipment to buy – they cannot run an office, especially in the New York metropolitan area, and take time to talk to patients. So as a result, doctors are seeing 35 patients instead of 15, and that is the reason there is no doctor/patient relationship.

You’ve been to Washington and understand the public policy aspects of health care reform. Has the debate been constructive, and is true reform possible?

For me, the debate has been on the right issues. The media, and especially some of the conservative networks, have misrepresented it, largely because of pressure from the insurance and pharmaceutical industries. This administration genuinely wants to improve medical care and make it available to people who don’t have it. It’s unconscionable that 30 to 50 million people don’t have insurance. Sure, if they have a heart attack, they get taken to the emergency room. But the time to intervene is when you develop symptoms that are an indication of early disease and uninsured people have no access to a doctor to interpret that and stop it right then and there. It has been said that 50,000 people die every year who should not have had to if they had early care. The reform is not perfect and once it is enacted, there will be modifications, but the goal is delivery of medical care, and I think their motivation is the right one.

In publishing an autobiography, some might think you are ready to slow down, but you still have a passion for your work.

I work full time. I’m 83, and my father died at 83, but I see patients every day. I work at night. I write. I’m working as hard as I did when I was 30. If something happens and I can’t do it anymore, I won’t. But as long as I feel like it, I’m going to stay – there is nothing I’d rather do.•